Heuristic algorithms: Difference between revisions

AnmolSingh (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

AnmolSingh (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

====Example 1: Scheduling Problem==== | ====Example 1: Scheduling Problem==== | ||

''You are given a set of N schedules of lectures for a single day at a university. The schedule for a specific lecture is of the form (s time, f time) where s time represents the start time for that lecture and similarly, the f time represents the finishing time. Given a list of N lecture schedules, we need to select maximum set of lectures to be held out during the day such that none of the lectures overlaps with one another i.e. if lecture Li and Lj are included in our selection then the start time of j >= finish time of i or vice versa.<ref>"Greedy Algorithms Explained With Examples". Freecodecamp.Org, 2020, https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/what-is-a-greedy-algorithm/ | ''You are given a set of N schedules of lectures for a single day at a university. The schedule for a specific lecture is of the form (s time, f time) where s time represents the start time for that lecture and similarly, the f time represents the finishing time. Given a list of N lecture schedules, we need to select maximum set of lectures to be held out during the day such that none of the lectures overlaps with one another i.e. if lecture Li and Lj are included in our selection then the start time of j >= finish time of i or vice versa.<ref>"Greedy Algorithms Explained With Examples". Freecodecamp.Org, 2020, https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/what-is-a-greedy-algorithm/.</ref>'' | ||

Solution: The most optimal solution to this would be to consider the earliest finishing time first. We sort the intervals according to increasing order of their finishing times and then we start selecting intervals from the very beginning. The pseudo-code is as follows: | Solution: The most optimal solution to this would be to consider the earliest finishing time first. We sort the intervals according to increasing order of their finishing times and then we start selecting intervals from the very beginning. The pseudo-code is as follows: | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Local Search method follows an iterative approach where we start with some initial solution, explore the neighbourhood of the current solution, and then replace the current solution with a better solution. For this method, the “travelling salesman problem” would follow the heuristic in which a solution is a cycle containing all nodes of the graph and the target is to minimize the total length of the cycle. | Local Search method follows an iterative approach where we start with some initial solution, explore the neighbourhood of the current solution, and then replace the current solution with a better solution. For this method, the “travelling salesman problem” would follow the heuristic in which a solution is a cycle containing all nodes of the graph and the target is to minimize the total length of the cycle. | ||

====Example Problem | ==== Example Problem <ref> Eiselt, Horst A et al. Integer Programming And Network Models. Springer, 2011.</ref> ==== | ||

Suppose that the problem P is to find an optimal ordering of N jobs in a manufacturing system. A solution to this problem can be described as an N-vector of job numbers, in which the position of each job in the vector defines the order in which the job will be processed. For example, [3, 4, 1, 6, 5, 2] is a possible ordering of 6 jobs, where job 3 is processed first, followed by job 4, then job 1, and so on, finishing with job 2. Define now M as the set of moves that produce new orderings by the swapping of any two jobs. For example, [3, 1, 4, 6, 5, 2] is obtained by swapping the positions of jobs 4 and 1. | Suppose that the problem P is to find an optimal ordering of N jobs in a manufacturing system. A solution to this problem can be described as an N-vector of job numbers, in which the position of each job in the vector defines the order in which the job will be processed. For example, [3, 4, 1, 6, 5, 2] is a possible ordering of 6 jobs, where job 3 is processed first, followed by job 4, then job 1, and so on, finishing with job 2. Define now M as the set of moves that produce new orderings by the swapping of any two jobs. For example, [3, 1, 4, 6, 5, 2] is obtained by swapping the positions of jobs 4 and 1. | ||

==Popular Heuristic Algorithms == | ==Popular Heuristic Algorithms== | ||

=== Genetic Algorithm=== | ===Genetic Algorithm=== | ||

The term Genetic Algorithm was first used by John Holland <ref>J.H. Holland (1975) ''Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems,'' University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan; re-issued by MIT Press (1992).</ref> They are designed to mimic the Darwinian theory of evolution, which states that populations of species evolve to produce more complex organisms and fitter for survival on Earth. Genetic algorithms operate on string structures, like biological structures, which are evolving in time according to the rule of survival of the fittest by using a randomized yet structured information exchange. Thus, in every generation, a new set of strings is created, using parts of the fittest members of the old set. <ref>Optimal design of heat exchanger networks, Editor(s): Wilfried Roetzel, Xing Luo, Dezhen Chen, Design and Operation of Heat Exchangers and their Networks, Academic Press, 2020, Pages 231-317, <nowiki>ISBN 9780128178942</nowiki>, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817894-2.00006-6</nowiki>.</ref> The algorithm terminates when the satisfactory fitness level has been reached for the population or the maximum generations have been reached. The typical steps are <ref>Wang FS., Chen LH. (2013) Genetic Algorithms. In: Dubitzky W., Wolkenhauer O., Cho KH., Yokota H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Springer, New York, NY. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9863-7_412</nowiki> </ref>: | The term Genetic Algorithm was first used by John Holland <ref>J.H. Holland (1975) ''Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems,'' University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan; re-issued by MIT Press (1992).</ref> They are designed to mimic the Darwinian theory of evolution, which states that populations of species evolve to produce more complex organisms and fitter for survival on Earth. Genetic algorithms operate on string structures, like biological structures, which are evolving in time according to the rule of survival of the fittest by using a randomized yet structured information exchange. Thus, in every generation, a new set of strings is created, using parts of the fittest members of the old set. <ref>Optimal design of heat exchanger networks, Editor(s): Wilfried Roetzel, Xing Luo, Dezhen Chen, Design and Operation of Heat Exchangers and their Networks, Academic Press, 2020, Pages 231-317, <nowiki>ISBN 9780128178942</nowiki>, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817894-2.00006-6</nowiki>.</ref> The algorithm terminates when the satisfactory fitness level has been reached for the population or the maximum generations have been reached. The typical steps are <ref>Wang FS., Chen LH. (2013) Genetic Algorithms. In: Dubitzky W., Wolkenhauer O., Cho KH., Yokota H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Springer, New York, NY. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9863-7_412</nowiki> </ref>: | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

===Tabu Search Algorithm=== | ===Tabu Search Algorithm=== | ||

Tabu search (TS) is a heuristic algorithm created by Fred Glover <ref>Fred Glover (1986). "Future Paths for Integer Programming and Links to Artificial Intelligence". Computers and Operations Research. '''13''' (5): 533–549. doi:10.1016/0305-0548(86)90048-1)</ref | Tabu search (TS) is a heuristic algorithm created by Fred Glover <ref>Fred Glover (1986). "Future Paths for Integer Programming and Links to Artificial Intelligence". Computers and Operations Research. '''13''' (5): 533–549. doi:10.1016/0305-0548(86)90048-1)</ref> using a gradient-descent search with memory techniques to avoid cycling for determining an optimal solution. It does so by forbidding or penalizing moves which take the solution, in the next iteration, to points in the solution space previously visited. The algorithm spends some memory to keep a Tabu list of forbidden moves, which are the moves of the previous iterations or moves that might be considered unwanted. A general algorithm is as follows <ref>Optimization of Preventive Maintenance Program for Imaging Equipment in Hospitals, Editor(s): Zdravko Kravanja, Miloš Bogataj, Computer-Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, Volume 38, 2016, Pages 1833-1838, ISSN 1570-7946, <nowiki>ISBN 9780444634283</nowiki>, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63428-3.50310-6</nowiki>.</ref>: | ||

1. Select an initial solution ''s''<sub>0</sub> ∈ ''S''. Initialize the Tabu List ''L''<sub>0</sub> = ∅ and select a list tabu size. Establish ''k'' = 0. | 1. Select an initial solution ''s''<sub>0</sub> ∈ ''S''. Initialize the Tabu List ''L''<sub>0</sub> = ∅ and select a list tabu size. Establish ''k'' = 0. | ||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

4. Stop if a condition of termination is reached, else, ''k'' = ''k'' + 1 and return to 1 | 4. Stop if a condition of termination is reached, else, ''k'' = ''k'' + 1 and return to 1 | ||

====Example: The Classical Vehicle Routing Problem | ==== Example: The Classical Vehicle Routing Problem <ref>Glover, Fred, and Gary A Kochenberger. Handbook Of Metaheuristics. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003.</ref> ==== | ||

''Vehicle Routing Problems'' have very important applications in distribution management and have become some of the most studied problems in the combinatorial optimization literature. These include several Tabu Search implementations that currently rank among the most effective. The ''Classical Vehicle Routing Problem'' (CVRP) is the basic variant in that class of problems. It can formally be defined as follows. Let ''G'' = (''V, A'') be a graph where ''V'' is the vertex set and ''A'' is the arc set. One of the vertices represents the ''depot'' at which a fleet of identical vehicles of capacity ''Q'' is based, and the other vertices customers that need to be serviced. With each customer vertex v<sub>i</sub> are associated a demand q<sub>i</sub> and a service time t<sub>i</sub>. With each arc (v<sub>i</sub>, v<sub>j</sub>) of ''A'' are associated a cost c<sub>ij</sub> and a travel time t<sub>ij</sub>. The CVRP consists of finding a set of routes such that: | ''Vehicle Routing Problems'' have very important applications in distribution management and have become some of the most studied problems in the combinatorial optimization literature. These include several Tabu Search implementations that currently rank among the most effective. The ''Classical Vehicle Routing Problem'' (CVRP) is the basic variant in that class of problems. It can formally be defined as follows. Let ''G'' = (''V, A'') be a graph where ''V'' is the vertex set and ''A'' is the arc set. One of the vertices represents the ''depot'' at which a fleet of identical vehicles of capacity ''Q'' is based, and the other vertices customers that need to be serviced. With each customer vertex v<sub>i</sub> are associated a demand q<sub>i</sub> and a service time t<sub>i</sub>. With each arc (v<sub>i</sub>, v<sub>j</sub>) of ''A'' are associated a cost c<sub>ij</sub> and a travel time t<sub>ij</sub>. The CVRP consists of finding a set of routes such that: | ||

Revision as of 12:53, 25 November 2020

Author: Anmol Singh (as2753)

Steward: Fengqi You, Allen Yang

Introduction

In mathematical programming, a heuristic algorithm is a procedure that determines near-optimal solutions to an optimization problem. However, this is achieved by trading optimality, completeness, accuracy, or precision for speed. [1] Nevertheless, heuristics is a widely used technique for a variety of reasons:

- Problems that do not have an exact solution or for which the formulation is unknown

- The computation of a problem is computationally intensive

- Calculation of bounds on the optimal solution in branch and bound solution processes

Methodology

Optimization heuristics can be categorized into two broad classes depending on the way the solution domain is organized:

Construction methods (Greedy algorithms)

The greedy algorithm works in phases, where the algorithm makes the optimal choice at each step as it attempts to find the overall optimal way to solve the entire problem. [2] It is a technique used to solve the famous “travelling salesman problem” where the heuristic followed is: "At each step of the journey, visit the nearest unvisited city."

Example 1: Scheduling Problem

You are given a set of N schedules of lectures for a single day at a university. The schedule for a specific lecture is of the form (s time, f time) where s time represents the start time for that lecture and similarly, the f time represents the finishing time. Given a list of N lecture schedules, we need to select maximum set of lectures to be held out during the day such that none of the lectures overlaps with one another i.e. if lecture Li and Lj are included in our selection then the start time of j >= finish time of i or vice versa.[3]

Solution: The most optimal solution to this would be to consider the earliest finishing time first. We sort the intervals according to increasing order of their finishing times and then we start selecting intervals from the very beginning. The pseudo-code is as follows:

function interval_scheduling_problem(requests)

schedule \gets \{\}

while requests is not yet empty

choose a request i_r \in requests that has the lowest finishing time

schedule \gets schedule \cup \{i_r\}

delete all requests in requests that are not compatible with i_r

end

return schedule

end

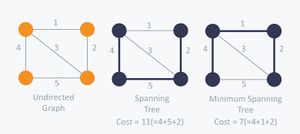

Example 2: The Minimum Spanning Tree

A spanning tree of the graph G=(V, E) is a tree that spans G (that is, it includes every vertex of G) and is a subgraph of G (every edge in the tree belongs to G). The cost of the spanning tree is the sum of the weights of all the edges in the tree. There can be many spanning trees, however, the minimum spanning tree is the spanning tree where the cost is minimum among all the spanning trees. Minimum spanning tree has direct application in the design of networks.

Local Search methods

Local Search method follows an iterative approach where we start with some initial solution, explore the neighbourhood of the current solution, and then replace the current solution with a better solution. For this method, the “travelling salesman problem” would follow the heuristic in which a solution is a cycle containing all nodes of the graph and the target is to minimize the total length of the cycle.

Example Problem [5]

Suppose that the problem P is to find an optimal ordering of N jobs in a manufacturing system. A solution to this problem can be described as an N-vector of job numbers, in which the position of each job in the vector defines the order in which the job will be processed. For example, [3, 4, 1, 6, 5, 2] is a possible ordering of 6 jobs, where job 3 is processed first, followed by job 4, then job 1, and so on, finishing with job 2. Define now M as the set of moves that produce new orderings by the swapping of any two jobs. For example, [3, 1, 4, 6, 5, 2] is obtained by swapping the positions of jobs 4 and 1.

Popular Heuristic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithm

The term Genetic Algorithm was first used by John Holland [6] They are designed to mimic the Darwinian theory of evolution, which states that populations of species evolve to produce more complex organisms and fitter for survival on Earth. Genetic algorithms operate on string structures, like biological structures, which are evolving in time according to the rule of survival of the fittest by using a randomized yet structured information exchange. Thus, in every generation, a new set of strings is created, using parts of the fittest members of the old set. [7] The algorithm terminates when the satisfactory fitness level has been reached for the population or the maximum generations have been reached. The typical steps are [8]:

1. Choose an initial population of candidate solutions

2. Calculate the fitness, how well the solution is, of each individual

3. Perform crossover from the population. The operation is to randomly choose some pair of individuals as parents and exchange so parts from the parents to generate new individuals

4. Mutation is to randomly change some individuals to create other new individuals

5. Evaluate the fitness of the offspring

6. Select the survive individuals

7. Proceed from 3 if the termination criteria have not been reached

Genetic algorithms have been applied in the fields of bioinformatics, computational biology, and systems biology. [9]

Tabu Search Algorithm

Tabu search (TS) is a heuristic algorithm created by Fred Glover [10] using a gradient-descent search with memory techniques to avoid cycling for determining an optimal solution. It does so by forbidding or penalizing moves which take the solution, in the next iteration, to points in the solution space previously visited. The algorithm spends some memory to keep a Tabu list of forbidden moves, which are the moves of the previous iterations or moves that might be considered unwanted. A general algorithm is as follows [11]:

1. Select an initial solution s0 ∈ S. Initialize the Tabu List L0 = ∅ and select a list tabu size. Establish k = 0.

2. Determine the neighborhood feasibility N(sk) that excludes inferior members of the tabu list Lk.

3. Select the next movement sk + 1 from N(Sk) or Lk if there is a better solution and update Lk + 1

4. Stop if a condition of termination is reached, else, k = k + 1 and return to 1

Example: The Classical Vehicle Routing Problem [12]

Vehicle Routing Problems have very important applications in distribution management and have become some of the most studied problems in the combinatorial optimization literature. These include several Tabu Search implementations that currently rank among the most effective. The Classical Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP) is the basic variant in that class of problems. It can formally be defined as follows. Let G = (V, A) be a graph where V is the vertex set and A is the arc set. One of the vertices represents the depot at which a fleet of identical vehicles of capacity Q is based, and the other vertices customers that need to be serviced. With each customer vertex vi are associated a demand qi and a service time ti. With each arc (vi, vj) of A are associated a cost cij and a travel time tij. The CVRP consists of finding a set of routes such that:

1. Each route begins and ends at the depot

2. Each customer is visited exactly once by exactly one route

3. The total demand of the customers assigned to each route does not exceed Q

4. The total duration of each route (including travel and service times) does not exceed a specified value L

5. The total cost of the routes is minimized

A feasible solution for the problem thus consists in a partition of the customers into m groups, each of total demand no larger than Q, that are sequenced to yield routes (starting and ending at the depot) of duration no larger than L.

Simulated Annealing Algorithm

The Simulated Annealing Algorithm was developed by Kirkpatrick et. al. in 1983 [13] and is based on the analogy of ideal crystals in thermodynamics. The annealing process in metallurgy can make particles arrange themselves in the position with minima potential as the temperature is slowly decreased. The Simulation Annealing algorithm mimics this mechanism and uses the objective function of an optimization problem instead of the energy of a material to arrive at a solution. A general algorithm is as follows [14] :

1. Fix initial temperature (T0)

2. Generate starting point x0 (this is the best point X* at present)

3. Generate randomly point XS (neighboring point)

4. Accept XS as X* (currently best solution) if an acceptance criterion is met. This must be such condition that the probability of accepting a worse point is greater than zero, particularly at higher temperatures

5. If an equilibrium condition is satisfied, go to (6), otherwise jump back to (3).

6. If termination conditions are not met, decrease temperature according to certain cooling scheme and jump back to (1). If termination conditions are satisfied, stop calculations accepting current best value X* as final (‘optimal’) solution.

References

- ↑ Eiselt, Horst A et al. Integer Programming And Network Models. Springer, 2011.

- ↑ Moore, Karleigh et al. "Greedy Algorithms | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki". Brilliant.Org, 2020, https://brilliant.org/wiki/greedy-algorithm/.

- ↑ "Greedy Algorithms Explained With Examples". Freecodecamp.Org, 2020, https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/what-is-a-greedy-algorithm/.

- ↑ “Minimum Spanning Tree Tutorials & Notes: Algorithms.” HackerEarth, www.hackerearth.com/practice/algorithms/graphs/minimum-spanning-tree/tutorial/.

- ↑ Eiselt, Horst A et al. Integer Programming And Network Models. Springer, 2011.

- ↑ J.H. Holland (1975) Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan; re-issued by MIT Press (1992).

- ↑ Optimal design of heat exchanger networks, Editor(s): Wilfried Roetzel, Xing Luo, Dezhen Chen, Design and Operation of Heat Exchangers and their Networks, Academic Press, 2020, Pages 231-317, ISBN 9780128178942, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817894-2.00006-6.

- ↑ Wang FS., Chen LH. (2013) Genetic Algorithms. In: Dubitzky W., Wolkenhauer O., Cho KH., Yokota H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9863-7_412

- ↑ Larranaga P, Calvo B, Santana R, Bielza C, Galdiano J, Inza I, Lozano JA, Armananzas R, Santafe G, Perez A, Robles V (2006) Machine learning in bioinformatics. Brief Bioinform 7(1):86–112

- ↑ Fred Glover (1986). "Future Paths for Integer Programming and Links to Artificial Intelligence". Computers and Operations Research. 13 (5): 533–549. doi:10.1016/0305-0548(86)90048-1)

- ↑ Optimization of Preventive Maintenance Program for Imaging Equipment in Hospitals, Editor(s): Zdravko Kravanja, Miloš Bogataj, Computer-Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, Volume 38, 2016, Pages 1833-1838, ISSN 1570-7946, ISBN 9780444634283, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63428-3.50310-6.

- ↑ Glover, Fred, and Gary A Kochenberger. Handbook Of Metaheuristics. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C., & Vecchi, M. (1983). Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science, 220(4598), 671-680. Retrieved November 25, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1690046

- ↑ Brief review of static optimization methods, Editor(s): Stanisław Sieniutycz, Jacek Jeżowski, Energy Optimization in Process Systems and Fuel Cells (Third Edition), Elsevier, 2018, Pages 1-41, ISBN 9780081025574, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102557-4.00001-3.