Momentum

Authors: Thomas Lee, Greta Gasswint, Elizabeth Henning (SYSEN5800 Fall 2021)

Introduction

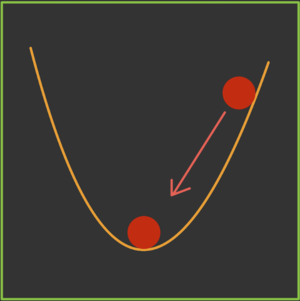

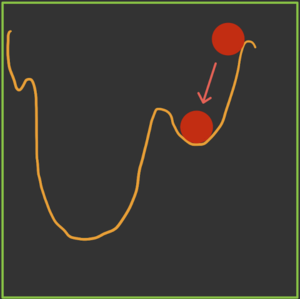

Momentum is an extension to the gradient descent optimization algorithm that builds inertia in a search direction to overcome local minima and oscillation of noisy gradients[1]. It is based on the same concept of momentum in physics. A classic example is a ball rolling down a hill that gathers enough momentum to overcome a plateau region and make it to a global minima instead of getting stuck at a local minima. Momentum adds history to the parameter updates which significantly accelerates the optimization process. Momentum controls the amount of history to include in the update equation via a hyperparameter[1]. This hyperparameter is a value ranging from 0 to 1. A momentum of 0 is equivalent to gradient descent without momentum[1]. A higher momentum value means more gradients from the past (history) are considered[2].

Theory, methodology, and/or algorithmic discussions

Definition

hi

Algorithm

The main idea behind momentum is to compute an exponentially weighted average of the gradients and use that to update the weights.

In gradient descent (stochastic) without momentum, the update rule at each iteration is given by:

W = W - dW

Where:

- W denotes the parameters to the cost function

- dW is the gradient indicating which direction to decrease the cost function by

- is the hyperparameter representing the learning rate

In gradient descent (stochastic) with momentum, the update rule at each iteration is given by:

V = βV + (1-β)dW

W = W - V

Where:

- β is a new hyperparameter that denotes the momentum constant

Problems with Gradient Descent

With gradient descent, a weight update at time t is given by the learning rate and gradient at that exact moment[2]. It doesn't not consider previous steps when searching.

This results in two issues:

- Unlike convex functions, a nonconvex cost function can have many local minima's meaning the first local minima found is not guaranteed to be the global minima. At the local minima, the gradient of the cost function will be very small resulting in no weight updates. Because of this, gradient descent will get stuck and fail to find the most optimal solution.

- Gradient descent can be noisy with many oscillations which results in a larger number of iterations needed to reach convergence.

Momentum is able to solve both of these issues but using an exponentially weighted average of the gradients to update the weights at each iteration. This method also prevents gradients of previous iterations to be weight equally. With an exponential weighted average, recent gradients are given more weightage than previous gradients. This can be seen in the numerical example below.

Another heading

hi

Another heading

hi

Graphical Explanation

hi

hi

hi

another header

- hi

another heading

- Blah:

Some Example

- More text

Numerical Example

To demonstrate the use of momentum in the context of gradient descent, minimize the following function:

This is a very stretched ellipsoid objective function with a minimum at (0,0). The gradient in the direction of changes at a much faster rate than due to the stretched nature of this function. Using gradient descent without momentum presents a challenge for selecting a learning rate. A small learning rate guarantees convergence in the direction, but will converge very slowly in the direction which is an issue. The alternative is a higher learning rate, which runs the risk of diverging in but will converge much quicker in the direction. The following graph shows the steps for solving this problem using a learning rate of 0.4.

INSERT GRAPH HERE

Applications

Some example

- An example of this is

Conclusion

hi