AdaGrad: Difference between revisions

| (57 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{bmatrix} x_{t+1}^{(2)} \\ x_{t+1}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ x_{t+1}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_{t}^{(2)} \\ x_{t}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ x_{t}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} - \eta \begin{bmatrix} g_{t}^{(2)} \\ g_{t}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ g_{t}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} </math> | <math display="block">\begin{bmatrix} x_{t+1}^{(2)} \\ x_{t+1}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ x_{t+1}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_{t}^{(2)} \\ x_{t}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ x_{t}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} - \eta \begin{bmatrix} g_{t}^{(2)} \\ g_{t}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ g_{t}^{(m)} \end{bmatrix} </math> | ||

=== AdaGrad Update === | === AdaGrad Update Rule === | ||

The general AdaGrad update rule is given by: | The general AdaGrad update rule is given by: | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

An estimate for the uncentered second moment of the objective function's gradient is given by the following expression: | An estimate for the uncentered second moment of the objective function's gradient is given by the following expression: | ||

<math>v = \frac{1}{t} \sum_{\tau=1}^t | <math>v = \frac{1}{t} \sum_{\tau=1}^t g_{\tau}g_{\tau}^{\top}</math> | ||

which is similar to the definition of matrix <math>G_t</math>, used in AdaGrad's update rule. Noting that, AdaGrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter proportionally to the inverse of the gradient's variance for every parameter. This leads to the main advantages of AdaGrad: | which is similar to the definition of matrix <math>G_t</math>, used in AdaGrad's update rule. Noting that, AdaGrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter proportionally to the inverse of the gradient's variance for every parameter. This leads to the main advantages of AdaGrad: | ||

# Parameters associated with low frequency features tend to have larger learning rates than parameters associated with high frequency features. | # Parameters associated with low-frequency features tend to have larger learning rates than parameters associated with high-frequency features. | ||

# Step-sizes in directions with high gradient variance are lower than the step-sizes in directions with low gradient variance. Geometrically, the step-sizes tend to decrease proportionally to the curvature of the stochastic objective function. | # Step-sizes in directions with high gradient variance are lower than the step-sizes in directions with low gradient variance. Geometrically, the step-sizes tend to decrease proportionally to the curvature of the stochastic objective function. | ||

which favor the convergence rate of the algorithm. | which favor the convergence rate of the algorithm. | ||

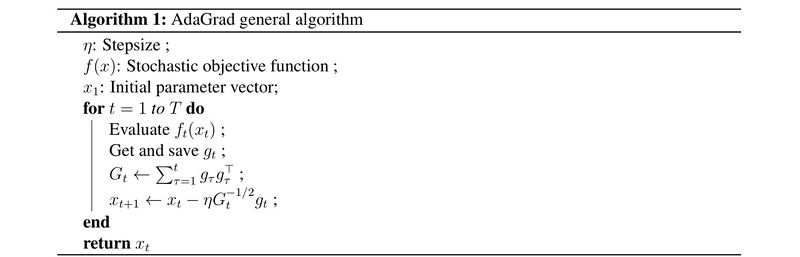

=== Algorithm === | === Algorithm === | ||

The general version of the AdaGrad algorithm is presented in the pseudocode below. The update step within the for loop can be modified with the version that uses the diagonal of <math>G_t</math>. | The general version of the AdaGrad algorithm is presented in the pseudocode below. The update step within the for loop can be modified with the version that uses the diagonal of <math>G_t</math>. | ||

[[File:AdaGrad | [[File:PseudoCode tau.jpg|800px|frameless|center|AdaGrad algorithm.]] | ||

=== Variants === | |||

One main disadvantage of AdaGrad is that it can be sensitive to the initial conditions of the parameters; for instance, if the initial gradients are large, the learning rates will be low for the remaining training. Additionally, the unweighted accumulation of gradients in <math>G_t</math> happens from the beginning of training, so after some training steps, the learning rate could approach zero without arriving at good local optima <ref name=":2">Zeiler, M. D. (2012). Adadelta: an adaptive learning rate method. ''arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.5701''.</ref>. Therefore, even with adaptative learning rates for each parameter, AdaGrad can be sensitive to the choice of global learning rate <math>\eta</math>. Some variants of AdaGrad have been proposed in the literature <ref name=":2" /> <ref name=":3">Mukkamala, M. C., & Hein, M. (2017, July). Variants of rmsprop and adagrad with logarithmic regret bounds. In ''International Conference on Machine Learning'' (pp. 2545-2553). PMLR.</ref> to overcome this and other problems, arguably the most popular one is AdaDelta. | |||

==== AdaDelta ==== | |||

AdaDelta is an algorithm based on AdaGrad that tackles the disadvantages mentioned before. Instead of accummulating the gradient in <math>G_t</math> over all time from <math>\tau = 1 </math> to <math>\tau = t</math>, AdaDelta takes an exponential weighted average of the following form: | |||

<math display="block">G_t = \rho G_{t-1} + (1-\rho) g_tg_t^{\top}</math> | |||

where <math>\rho </math> is an hyperparameter, known as the decay rate, that controls the importance given to past observations of the squared gradient. Therefore, in contrast with AdaGrad, with AdaDelta the increase on <math>G_t</math> is under control. Typicall choices for the decay rate <math>\rho </math> are 0.95 or 0.90, which are the default choices for the AdaDelta optimizer in TensorFlow<ref>''tf.keras.optimizers.Adadelta | TensorFlow Core v2.7.0''. (2021). Tf.Keras.Optimizers.Adadelta. <nowiki>https://www.tensorflow.org/api_docs/python/tf/keras/optimizers/Adadelta</nowiki></ref> and PyTorch<ref>''Adadelta — PyTorch 1.10.0 documentation''. (2019). ADADELTA. <nowiki>https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.optim.Adadelta.html</nowiki></ref>, respectively. | |||

Additionally, in AdaDelta the squared updates are accumulated with a running average with parameter <math>\rho</math><ref name=":2" />: | |||

<math display="block">E[\Delta x^2]_t = \rho E[\Delta x^2]_{t-1} + (1-\rho) \Delta x^2_t</math> | |||

where, | |||

<math display="block">\Delta x_t = - (\sqrt{\Delta x_{t-1} + \epsilon}) G_t^{-1/2} g_t</math> | |||

so the update rule in AdaDelta is given by: | |||

<math display="block">\Delta x_{t+1} = x_t + \Delta x_t</math> | |||

==== RMSprop ==== | |||

[[RMSProp|RMSprop]] is identical to AdaDelta without the running average for the parameter updates. Therefore, the update rule for this algorithm is the same as AdaGrad with <math>G_t</math> calculated as done for AdaDelta (<math>G_t = \rho G_{t-1} + (1-\rho) g_tg_t^{\top}</math>)<ref name=":7">Tieleman, T. and Hinton, G. (2012). Lecture 6.5 - RMSProp, COURSERA: Neural Networks for Machine Learning. | |||

Technical report.</ref>. | |||

=== Regret Bound === | === Regret Bound === | ||

| Line 63: | Line 90: | ||

<math>R(t) = \sum_{t= 1}^T f_{t}(x_t) - \sum_{t=1}^t f_{t}(x^*)</math> | <math>R(t) = \sum_{t= 1}^T f_{t}(x_t) - \sum_{t=1}^t f_{t}(x^*)</math> | ||

where <math>x^*</math>is the set of optimal parameters. AdaGrad has a regret bound of order <math>O(\sqrt{T})</math>, which leads to the convergence rate of order <math>O(1/\sqrt{T})</math>, and the convergence guarantee (<math display="inline">\lim_{T \to \infty} R(T)/T = 0</math>). The detailed proof and assumptions for this bound can be found in the original journal paper<ref name=":0" />. | where <math>x^*</math>is the set of optimal parameters. AdaGrad has a regret bound of order <math>O(\sqrt{T})</math>, which leads to the convergence rate of order <math>O(1/\sqrt{T})</math>, and the convergence guarantee (<math display="inline">\lim_{T \to \infty} R(T)/T = 0</math>). The detailed proof and assumptions for this bound can be found in the original journal paper<ref name=":0" />. However, with some modifications to the original AdaGrad algorithm, SC-AdaGrad<ref name=":3" /> shows a logarithmic regret bound (<math>O(\ln T)</math>). | ||

Considering the dimension <math>d</math> of the gradient vectors, AdaGrad has a regret bound of order <math>O(\sqrt{dT})</math>. Nevertheless, for the special case when gradient vectors are sparse, AdaGrad has a regret of an order <math>O(\ln d\sqrt{T})</math><ref name=":0" />. Therefore, when gradient vectors are sparse, AdaGrad's regret bound can be exponentially better than SGD (which has a regret bound equal to <math>O(\sqrt{dT})</math> in that setting). | |||

=== Comparison with Other Gradient-based Methods === | |||

AdaGrad is an improved version of regular SGD; it includes second-order information in the parameter updates and provides adaptative learning rates for each parameter. However, it doesn't incorporate momentum, which could improve convergence rates. An algorithm closely related to AdaGrad that incorporates momentum is [[Adam|Adam]]. | |||

==== Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) ==== | |||

[[Stochastic gradient descent|SGD's]] update rule is fairly simple: | |||

<math display="block">x_{t+1} = x_t - \eta g_t</math> | |||

so, in comparison with AdaGrad, SGD doesn't have an independent learning rate for each parameter and doesn't include second-order information from the accumulation of square gradients in <math>G_t</math> | |||

==== Adam ==== | |||

[[Adam|Adam]] includes estimates of the gradient's first and second uncentered moments in its update rule. The estimate for the first moment is a bias-corrected running average of the gradient, and the one for the second moment is equivalent to the one in AdaGrad. Therefore, for a particular set of hyperparameters, [[Adam|Adam]] is equivalent to AdaGrad<ref name=":1" />. | |||

== Numerical Example == | == Numerical Example == | ||

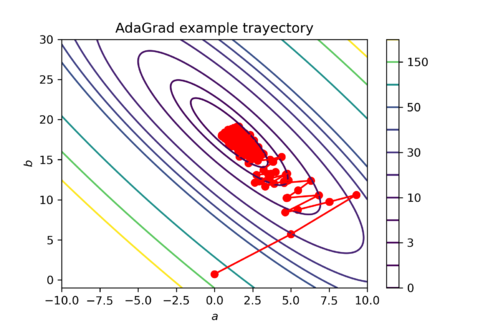

[[File:AdaGrad trayectory.png|thumb|493x493px|Figure 1. This figure shows a trajectory of parameter updates for the example presented in this section using AdaGrad. |alt=]]To illustrate how the parameter updates work in AdaGrad take the following numerical example The dataset consists of random generated obsevations <math>x,y </math> that follow the linear relationship:<math display="block">y = 20 \cdot x + \epsilon </math>where <math>\epsilon</math> is random noise. The first 5 obsevations are shown in the table below. | [[File:AdaGrad trayectory.png|thumb|493x493px|Figure 1. This figure shows a trajectory of parameter updates for the example presented in this section using AdaGrad. |alt=]]To illustrate how the parameter updates work in AdaGrad take the following numerical example. The dataset consists of random generated obsevations <math>x,y </math> that follow the linear relationship:<math display="block">y = 20 \cdot x + \epsilon </math>where <math>\epsilon</math> is random noise. The first 5 obsevations are shown in the table below. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!<math>x </math> | !<math>x </math> | ||

| Line 98: | Line 143: | ||

<math display="block">G_1 = \sum_{\tau=1}^1 g_1g_1^{\top} = \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 \\ -7.68 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 & -7.68 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 387.30 & 151.14\\ 151.14 & 58.98\end{bmatrix} </math>So the first parameter's update is calculated as follows: | <math display="block">G_1 = \sum_{\tau=1}^1 g_1g_1^{\top} = \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 \\ -7.68 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 & -7.68 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 387.30 & 151.14\\ 151.14 & 58.98\end{bmatrix} </math>So the first parameter's update is calculated as follows: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{bmatrix} a_2 \\ b_2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} 5 \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{387.30}} \\ 5\cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 58.98}} \end{bmatrix} \odot \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 \\ -7.68 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 5 \\ 5\end{bmatrix}</math>This process is repetated until convergence or for a fixed number of iterations <math>T</math>. An example AdaGrad update | <math display="block">\begin{bmatrix} a_2 \\ b_2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} 5 \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{387.30}} \\ 5\cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 58.98}} \end{bmatrix} \odot \begin{bmatrix} -19.68 \\ -7.68 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 5 \\ 5\end{bmatrix}</math>This process is repetated until convergence or for a fixed number of iterations <math>T</math>. An example AdaGrad update trajectory for this example is presented in Figure 1. Note that in Figure 1, the algorithm converges to a region close to <math>(a,b) = (0,20)</math>, which are the set of parameters that originated the obsevations in this example. | ||

== Applications == | == Applications == | ||

The AdaGrad family of algorithms is typically used in machine learning applications. Mainly, it is a good choice for deep learning models with sparse | The AdaGrad family of algorithms is typically used in machine learning applications. Mainly, it is a good choice for deep learning models with sparse gradients<ref name=":0" />, like [[wikipedia:Recurrent neural network|recurrent neural networks]] and [[wikipedia:Transformer (machine learning model)|transformer models]] for [[wikipedia:Natural language processing|natural language processing]]. However, one can apply it to any optimization problem with a differentiable cost function. | ||

Given its popularity and proven performance, different versions of AdaGrad are implemented in the leading deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch. Nevertheless, in practice, AdaGrad tends to be substituted by using the Adam algorithm; since, for a given choice of hyperparameters, Adam is equivalent to AdaGrad <ref name=":1" />. | |||

=== Natural Language Processing === | |||

Natural language processing (NLP) is an area of research concerned with the interactions between computers and human language. Multiple tasks fall within the giant umbrella of NLP, such as [[wikipedia:Sentiment analysis|sentiment analysis]], [[wikipedia:Automatic summarization|automatic summarization]], [[wikipedia:Machine translation|machine translation]], and [[wikipedia:Autocomplete|text completion]]. Deep learning models, like recurrent neural networks and transformer models<ref name=":9">Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., ... & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 5998-6008).</ref>, are the usual choices for these tasks, and one common issue faced when training is sparse gradients. Therefore, AdaGrad and Adam work better than standard SGD for that settings. | |||

== | == Conclusion == | ||

AdaGrad is a family of algorithms for stochastic optimization that uses a Hessian approximation of the cost function for the update rule. It uses that information to adapt different learning rates for the parameters associated with each feature. Their main two advantages are that: it assigns more significant learning rates to parameters related to low-frequency features, and the updates in directions of high curvature tend to be lower than those in low-curvature directions. Therefore, it works especially well for problems where the input features are sparse. AdaGrad is reasonably popular in the machine learning community, and it is implemented in the primary deep learning frameworks. In practice, the Adam algorithm is usually preferred over AdaGrad since, for a given choice of hyperparameters, Adam is equivalent to AdaGrad. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:03, 14 December 2021

Author: Daniel Villarraga (SYSEN 6800 Fall 2021)

Introduction

AdaGrad is a family of sub-gradient algorithms for stochastic optimization. The algorithms belonging to that family are similar to second-order stochastic gradient descend with an approximation for the Hessian of the optimized function. AdaGrad's name comes from Adaptative Gradient. Intuitively, it adapts the learning rate for each feature depending on the estimated geometry of the problem; particularly, it tends to assign higher learning rates to infrequent features, which ensures that the parameter updates rely less on frequency and more on relevance.

AdaGrad was introduced by Duchi et al.[1] in a highly cited paper published in the Journal of machine learning research in 2011. It is arguably one of the most popular algorithms for machine learning (particularly for training deep neural networks) and it influenced the development of the Adam algorithm[2].

Theory

The objective of AdaGrad is to minimize the expected value of a stochastic objective function, with respect to a set of parameters, given a sequence of realizations of the function. As with other sub-gradient-based methods, it achieves so by updating the parameters in the opposite direction of the sub-gradients. While standard sub-gradient methods use update rules with step-sizes that ignore the information from the past observations, AdaGrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter individually using the sequence of gradient estimates.

Definitions

: Stochastic objective function with parameters .

: Realization of stochastic objective at time step . For simplicity .

: The gradient of with respect to , formally . For simplicity, .

: Parameters at time step .

: The outer product of all previous subgradients, given by

Standard Sub-gradient Update

Standard sub-gradient algorithms update parameters according to the following rule:

AdaGrad Update Rule

The general AdaGrad update rule is given by:

Adaptative Learning Rate Effect

An estimate for the uncentered second moment of the objective function's gradient is given by the following expression:

which is similar to the definition of matrix , used in AdaGrad's update rule. Noting that, AdaGrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter proportionally to the inverse of the gradient's variance for every parameter. This leads to the main advantages of AdaGrad:

- Parameters associated with low-frequency features tend to have larger learning rates than parameters associated with high-frequency features.

- Step-sizes in directions with high gradient variance are lower than the step-sizes in directions with low gradient variance. Geometrically, the step-sizes tend to decrease proportionally to the curvature of the stochastic objective function.

which favor the convergence rate of the algorithm.

Algorithm

The general version of the AdaGrad algorithm is presented in the pseudocode below. The update step within the for loop can be modified with the version that uses the diagonal of .

Variants

One main disadvantage of AdaGrad is that it can be sensitive to the initial conditions of the parameters; for instance, if the initial gradients are large, the learning rates will be low for the remaining training. Additionally, the unweighted accumulation of gradients in happens from the beginning of training, so after some training steps, the learning rate could approach zero without arriving at good local optima [3]. Therefore, even with adaptative learning rates for each parameter, AdaGrad can be sensitive to the choice of global learning rate . Some variants of AdaGrad have been proposed in the literature [3] [4] to overcome this and other problems, arguably the most popular one is AdaDelta.

AdaDelta

AdaDelta is an algorithm based on AdaGrad that tackles the disadvantages mentioned before. Instead of accummulating the gradient in over all time from to , AdaDelta takes an exponential weighted average of the following form:

where is an hyperparameter, known as the decay rate, that controls the importance given to past observations of the squared gradient. Therefore, in contrast with AdaGrad, with AdaDelta the increase on is under control. Typicall choices for the decay rate are 0.95 or 0.90, which are the default choices for the AdaDelta optimizer in TensorFlow[5] and PyTorch[6], respectively.

Additionally, in AdaDelta the squared updates are accumulated with a running average with parameter [3]:

where,

so the update rule in AdaDelta is given by:

RMSprop

RMSprop is identical to AdaDelta without the running average for the parameter updates. Therefore, the update rule for this algorithm is the same as AdaGrad with calculated as done for AdaDelta ()[7].

Regret Bound

The regret is defined as:

where is the set of optimal parameters. AdaGrad has a regret bound of order , which leads to the convergence rate of order , and the convergence guarantee (). The detailed proof and assumptions for this bound can be found in the original journal paper[1]. However, with some modifications to the original AdaGrad algorithm, SC-AdaGrad[4] shows a logarithmic regret bound ().

Considering the dimension of the gradient vectors, AdaGrad has a regret bound of order . Nevertheless, for the special case when gradient vectors are sparse, AdaGrad has a regret of an order [1]. Therefore, when gradient vectors are sparse, AdaGrad's regret bound can be exponentially better than SGD (which has a regret bound equal to in that setting).

Comparison with Other Gradient-based Methods

AdaGrad is an improved version of regular SGD; it includes second-order information in the parameter updates and provides adaptative learning rates for each parameter. However, it doesn't incorporate momentum, which could improve convergence rates. An algorithm closely related to AdaGrad that incorporates momentum is Adam.

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

SGD's update rule is fairly simple:

so, in comparison with AdaGrad, SGD doesn't have an independent learning rate for each parameter and doesn't include second-order information from the accumulation of square gradients in

Adam

Adam includes estimates of the gradient's first and second uncentered moments in its update rule. The estimate for the first moment is a bias-corrected running average of the gradient, and the one for the second moment is equivalent to the one in AdaGrad. Therefore, for a particular set of hyperparameters, Adam is equivalent to AdaGrad[2].

Numerical Example

To illustrate how the parameter updates work in AdaGrad take the following numerical example. The dataset consists of random generated obsevations that follow the linear relationship:

| 0.39 | 9.83 |

| 0.10 | 2.27 |

| 0.30 | 5.10 |

| 0.35 | 6.32 |

| 0.85 | 15.50 |

The cost function is defined as . And an observation of the cost function at time step is given by , where are sampled from the obsevations. Finally, the subgradient is determined by:

Take a learning rate , initial parameters , and . For the first iteration of AdaGrad the subgradient is equal to:

and is:

Applications

The AdaGrad family of algorithms is typically used in machine learning applications. Mainly, it is a good choice for deep learning models with sparse gradients[1], like recurrent neural networks and transformer models for natural language processing. However, one can apply it to any optimization problem with a differentiable cost function.

Given its popularity and proven performance, different versions of AdaGrad are implemented in the leading deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch. Nevertheless, in practice, AdaGrad tends to be substituted by using the Adam algorithm; since, for a given choice of hyperparameters, Adam is equivalent to AdaGrad [2].

Natural Language Processing

Natural language processing (NLP) is an area of research concerned with the interactions between computers and human language. Multiple tasks fall within the giant umbrella of NLP, such as sentiment analysis, automatic summarization, machine translation, and text completion. Deep learning models, like recurrent neural networks and transformer models[8], are the usual choices for these tasks, and one common issue faced when training is sparse gradients. Therefore, AdaGrad and Adam work better than standard SGD for that settings.

Conclusion

AdaGrad is a family of algorithms for stochastic optimization that uses a Hessian approximation of the cost function for the update rule. It uses that information to adapt different learning rates for the parameters associated with each feature. Their main two advantages are that: it assigns more significant learning rates to parameters related to low-frequency features, and the updates in directions of high curvature tend to be lower than those in low-curvature directions. Therefore, it works especially well for problems where the input features are sparse. AdaGrad is reasonably popular in the machine learning community, and it is implemented in the primary deep learning frameworks. In practice, the Adam algorithm is usually preferred over AdaGrad since, for a given choice of hyperparameters, Adam is equivalent to AdaGrad.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Duchi, J., Hazan, E., & Singer, Y. (2011). Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. Journal of machine learning research, 12(7).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. (2014). Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Zeiler, M. D. (2012). Adadelta: an adaptive learning rate method. arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.5701.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mukkamala, M. C., & Hein, M. (2017, July). Variants of rmsprop and adagrad with logarithmic regret bounds. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 2545-2553). PMLR.

- ↑ tf.keras.optimizers.Adadelta | TensorFlow Core v2.7.0. (2021). Tf.Keras.Optimizers.Adadelta. https://www.tensorflow.org/api_docs/python/tf/keras/optimizers/Adadelta

- ↑ Adadelta — PyTorch 1.10.0 documentation. (2019). ADADELTA. https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.optim.Adadelta.html

- ↑ Tieleman, T. and Hinton, G. (2012). Lecture 6.5 - RMSProp, COURSERA: Neural Networks for Machine Learning. Technical report.

- ↑ Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., ... & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 5998-6008).

![{\displaystyle E[\Delta x^{2}]_{t}=\rho E[\Delta x^{2}]_{t-1}+(1-\rho )\Delta x_{t}^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/35358ea55a37e1c6780d5f60c69521eaf543e2fa)

![{\textstyle f(a,b)={\frac {1}{N}}\sum _{i=1}^{n}([a+b\cdot x_{i}]-y_{i})^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d86302234845f28e7123709faaa4cd93d7260f9d)

![{\displaystyle f_{t}(a,b)=([a+b\cdot x_{t}]-y_{t})^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6907c9197706539cecb74f1c2b7c4266b99690b1)

![{\displaystyle g_{t}={\begin{bmatrix}2([a_{t}+b_{t}\cdot x_{t}]-y_{t})\\2x_{t}([a_{t}+b_{t}\cdot x_{t}]-y_{t})\end{bmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e1b916a0cb18358a5697db2b4839a506fb886d26)

![{\displaystyle g_{1}={\begin{bmatrix}2([0+0\cdot 0.39]-9.84)\\2\cdot 0.39([0+0\cdot 0.39]-9.84)\end{bmatrix}}={\begin{bmatrix}-19.68\\-7.68\end{bmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f11843be8e8b85c9825f07d0c693a1927eb82c2b)